Thursday, July 16, 2009

"Unscientific America" and the case of Pluto

There has been a lot of web discussion about Chris Mooney and Sheril Kirshenbaum's new book, “Unscientific America” (particularly over PZ Myers review, see their response to PZ Myers here). I’d like to focus on one part from the beginning of the book, the one that got PZ exercised, that I think illustrates an important problem with the book. You can read the excerpt from the book that deals with the issue of the demotion of Pluto here.

There has been a lot of web discussion about Chris Mooney and Sheril Kirshenbaum's new book, “Unscientific America” (particularly over PZ Myers review, see their response to PZ Myers here). I’d like to focus on one part from the beginning of the book, the one that got PZ exercised, that I think illustrates an important problem with the book. You can read the excerpt from the book that deals with the issue of the demotion of Pluto here.[numerous t-shirt slogans omitted]So read a small sampling of the defiant T-shirt and bumper sticker slogans that emerged in late 2006 after the International Astronomical Union (IAU), meeting in Prague, opted to poke the public with a sharp stick. The union's general assembly voted to excommunicate the ninth planet from the solar system, thus abruptly stripping Pluto of a status as much cultural, historic, and even mythological as scientific.Here the IAU, as representative scientists, is shown as being antagonistic to the public. But why? Why is the Pluto decision “poking the public with a sharp stick? The IAU was making a ruling based on our scientific understanding to resolve a long standing problem. This ruling did not come out of nowhere and the lead-up was well publicised.

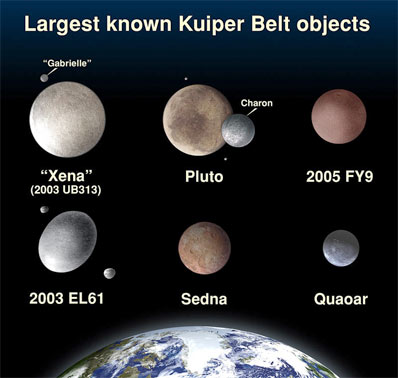

In the astronomers' defense, it had become increasingly difficult to justify calling Pluto a planet without doing the same for several other more recently discovered heavenly objects--one of which, the distant freezing rock now known as Eris (formerly "Xena"), turns out to be larger. But that didn't mean the experts had to fire Pluto from its previous place in the firmament. In defining the word "planet," they were arguably not so much engaged in science as a semantic exercise …....Keeping Pluto a planet was a lot more than semantics. Up until the notorious 2006 decision, there was no accepted definition of a planet. Also, by the 1990’s it was increasingly evident that Pluto was not like the other planets. It’s orbit was unusual, very much tilted to the plane of the other planets, and much more elliptical, even coming inside the orbit of Neptune at its closest approach to the Sun. Pluto was also very small, while it was originally thought to be 90% the size of Earth, subsequent study showed it was 2/3rds the size of Earth’s Moon. In the meantime, the Kuiper Belt objects had been discovered. Small icy objects with orbits similar to Pluto’s in inclination and distance. As time went on, larger and larger Kuiper Belt objects were discovered, approaching that of Pluto in size (eg Sedna). The Kuiper Belt object composition was also similar to that of Pluto.

It was increasingly obvious that Pluto was just a large Kuiper belt object and that sooner or later other icy worlds, the same size as Pluto or bigger, would turn up. As well, while the classical planets were thought to be formed from accretion of smaller objects, the Kuiper belt objects (including Pluto) were thought to be leftovers from the formation of the solar system. So Pluto had a different history to the classical planets. Spurred by this knowledge, from 1998 there were various attempts to create a definition of a planet that would deal with Pluto and the new Kuiper Belt bodies. Attempts to find a definition that would have a sensible physical definition and keep Pluto as a planet all failed.

It was increasingly obvious that Pluto was just a large Kuiper belt object and that sooner or later other icy worlds, the same size as Pluto or bigger, would turn up. As well, while the classical planets were thought to be formed from accretion of smaller objects, the Kuiper belt objects (including Pluto) were thought to be leftovers from the formation of the solar system. So Pluto had a different history to the classical planets. Spurred by this knowledge, from 1998 there were various attempts to create a definition of a planet that would deal with Pluto and the new Kuiper Belt bodies. Attempts to find a definition that would have a sensible physical definition and keep Pluto as a planet all failed. The issue was finally forced by the discovery of UB313 (Eris). It was (just) larger than Pluto, was it a planet? The IAU finally had to come up with a definition of a planet. After a number of attempts, a panel of notable scientists and writer Dava Sobel (Longitude, The Planets) provided a definition that was based on physical properties, and tried to avoid any arbitrariness. They proposed that a planet was anything that was large enough that gravity pulled it into a sphere. They then divided the Planets into Classical Planets (Mercury to Neptune) and Dwarf Planets (things like Pluto, Ceres and Eris) based on whether the planet was gravitationally dominant (ie was it big enough to sweep away all the floating junk in the planets local area, dwarf planets didn't).

The issue was finally forced by the discovery of UB313 (Eris). It was (just) larger than Pluto, was it a planet? The IAU finally had to come up with a definition of a planet. After a number of attempts, a panel of notable scientists and writer Dava Sobel (Longitude, The Planets) provided a definition that was based on physical properties, and tried to avoid any arbitrariness. They proposed that a planet was anything that was large enough that gravity pulled it into a sphere. They then divided the Planets into Classical Planets (Mercury to Neptune) and Dwarf Planets (things like Pluto, Ceres and Eris) based on whether the planet was gravitationally dominant (ie was it big enough to sweep away all the floating junk in the planets local area, dwarf planets didn't).Again, as you will note, the issue wasn’t one of semantics, but finding a set of physical properties of the objects that could separate planets from non-planets without an arbitrary dividing line. If Pluto was to be called a planet, then what definition would exclude the dozens of icy lumps in similar orbits that were a tad smaller? If you didn’t exclude them, then up to 20-40 planets would have been created. The public may have been ready for a 10th planet, but over 20? More than semantics were at stake here.

In the end, after a fair bit of argy-bargy, the definition of “Planet” adopted was one where an object was big enough to be spherical and have enough gravitational grunt to sweep up all the debris near it. Things that were merely spherical became dwarf planets. Pluto got demoted.

Why suddenly kick Pluto out of the planet fraternity after letting it stay in for nearly a century, ever since its 1930 discovery? "No do-overs," wrote one cartoonist..... how could this planetary crackup happen in the first place? Didn't the scientists involved foresee such an outcry from the public? Did they simply not care? Was the Pluto decision really scientifically necessary?

There was nothing sudden about it. Back in 1995 astronomer Dave Jewitt received death treats for suggesting that Pluto was just a Kuiper belt object. In 1998 the first serious attempts to define a planet went rumbling through the professional and amateur astronomical worlds, and listservs buzzed with debate. In 2001 Neil deGrasse Tyson cheekily put up an exhibit at the Hayden planetarium suggesting that Pluto should not be a planet. This was widely reported in tradition and electronic media. The issue arose again in 2004 with the discovery of Sedna, and yet again when Eris, larger than Pluto was discovered.

Previous attempts to define a planet that kept Pluto as a planet had failed, but now a ruling was absolutely required, otherwise Eris (and any other large transneptunian object subsequently discovered) would be in limbo. From the discovery of Eris to the fateful meeting in 2006 there was a well publicised debate.

It's not like this was not without precedent, for 40 years from around 1806 the solar system had 11 planets, Mercury to Uranus and Ceres, Pallas, Vesta and Juno (by 1845 there were 17). They were listed in professional and popular works on the planets and astronomy. More and more of the lumps of rocky rubble turned up, until there were nearly 100 of them. Then in 1846, in a parallel to the recent events, Neptune was discovered; Ceres, Pllas, Vesta and Juno were demoted to "minor planets" and everyone moved on.

The furor over Pluto is just one particularly colorful example of the rift that exists today between the world of science and the rest of our society.How? What is this meant to show? That scientists are mean? That seems to be one theme ("The International Astronomical Union (IAU)... opted to poke the public with a sharp stick", "Didn't the scientists involved foresee such an outcry from the public? Did they simply not care?"). Astronomers did forsee an outcry from the public, and they did care (especially as several of their own number had a strong attachment to Pluto s a planet). But they needed to make a decision, they had an object larger than Pluto, and they needed a definition of a planet to decide on its status, or Eris would have remained in scientific limbo. The Pluto decision was scientifically necessary.

Does it show that scientists are poor communicators? From 2001 on the debate over Pluto's status was accompanied by high visibility events such as Neil deGrasse Tyson's planetarium exhibit, which was well covered in the media. Listen to his story of receiving hate mail from 3rd graders here. The discovery of Sedna and then Eris were high profile events in which the question of Pluto's planet hood was raised with discussion of why a planetary determination was necessary. The lead up to the IAU meeting was covered in the traditional and electronic media. For example, Mike Brown the leader of the team that discovered Eris kept a rapidly updated web page and wrote popular articles for outlets such as the New York Times. The IAU issued press releases, had a large media presence and had a special presentation by Joycelyn Bell Burnell (the discover of Pulsars) to explain the significance and reasoning behind the decision that was made. What more could they do?

Is the point that the American public are woefully ignorant of science? We should be happy that they knew what Pluto was. From 1995 to 2009 nearly 50% of Americans did not know that Earth took a year to orbit the Sun, one in 5 Americans did not know that Earth orbits the Sun (don't get cocky non-Americans, the figures are similar for Europe and Australia

Is the point that the American public are woefully ignorant of science? We should be happy that they knew what Pluto was. From 1995 to 2009 nearly 50% of Americans did not know that Earth took a year to orbit the Sun, one in 5 Americans did not know that Earth orbits the Sun (don't get cocky non-Americans, the figures are similar for Europe and Australia So what, exactly, is Moony and Kirshenbaum's point? That scientists shouldn't have chosen a definition that excluded Pluto? They needed a rational, non-arbitrary demarcation, we had a choice between 8 planets and a bunch of smaller stuff, or something like 20+ planets based on rational definitions. I'm not sure that the public would be pleased with having to learn Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Ceres, Vesta, Pallas, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, Pluto, Charon, Orcus, Ixus, Quoarar, Sendna, Eris .... and so on as the solar systems planetary lineup. Either way, a non-arbitrary decision had to be made.

Was their point that scientists didn't try hard enough to get their points across? It's hard to see what more they could have done, they pursued all available avenues of public communication and this was riding on the coat-tails of very exciting discoveries that the public were interested in and had significant exposure in traditional media. How more high profile could they get?

To put this in perspective, NASA has an enormous outreach program, high profile impact because of the stunning nature of the subjects it covers (and people really like space exploration), flashy websites, stunning images, education sites and helpful animations. And STILL one in five Americans don't realise that Earth rotates around the Sun and around 50% don't realise that Earth takes a year to rotate around the Sun. If those simple facts can't be gotten across with a huge expenditure of money, how are ordinary astronomers with modest budgets going to get their ideas about Pluto across.

The most disturbing thing is that Mooney and Kirshenbaum should have known the history of the Pluto debate, the details are easily available and there are two substantial books about this. Mooney and Kirshenbaum's statements about the issues are almost completely wrong. If they can't something as simple as this right, what about the other issues in this book?

UPDATE: You can read the IAU's own document on communicating science at the 2006 "Pluto" meeting here (Warning 25 Mb document). The IAU put a lot of thought and resources (press releases, arranging journalist interviews, web links, web-based video and interviews etc.) into communicating science and the Pluto issue at this meeting. Not everything worked, but we can safely say that the public reaction occurred despite a large amount of outreach and communication on the part of the IAU and other astronomers.

Like all my Pluto Posts, this one should be read listening to Jimmy and the Keys "They Demoted Pluto".

And really, really listen to Neil deGrasse Tyson's talk on Pluto's demotion (It's really quite informative and amusing, according to him, Europeans did not have the same visceral reaction).

Read Govert Schilling's “The Hunt for Planet X” (ISBN: 978-0-387-77804-4) and Neil deGrasse Tyson's book The Pluto Files, The Demotion of a Planet (ISBN-13: 9780393065206).

Like all my Pluto Posts, this one should be read listening to Jimmy and the Keys "They Demoted Pluto".

And really, really listen to Neil deGrasse Tyson's talk on Pluto's demotion (It's really quite informative and amusing, according to him, Europeans did not have the same visceral reaction).

Read Govert Schilling's “The Hunt for Planet X” (ISBN: 978-0-387-77804-4) and Neil deGrasse Tyson's book The Pluto Files, The Demotion of a Planet (ISBN-13: 9780393065206).

Labels: Pluto, Science Blogging, science matters

Comments:

<< Home

No, the IAU did not HAVE to come up with a definition of planet; Pluto is NOT just another object in the Kuiper Belt; the IAU definition was created in a flawed, political process that violated its own bylaws, and was immediately opposed by hundreds of professional astronomers in a formal petition led by Dr. Alan Stern, Principal Investigator of NASA's New Horizons mission to Pluto.

Why do you refer people only to the books and web sites of Dr. Tyson and Mike Brown? What about "Is Pluto A Planet" by Dr. David Weintraub or "The Case for Pluto" by Alan Boyle? What about the Great Planet Debate, a far more open discussion held in August 2008 at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab in Laurel, MD, where in depth discussion made clear that this issue is not resolved and is far more complex that often portrayed. You do the public a disservice by referring people to only one side of an ongoing debate as "truth" when it is one interpretation of truth. It is acts like this that turn people off to science.

Pluto is not just another KBO. Unlike most, it is in a state of hydrostatic equilibrium, meaning it is large enough to be pulled into a round shape by its own gravity, a characteristic of planets and not shapeless asteroids and KBOs. The same is true of Eris. Why is there a problem with having 20 plus planets in our solar system, and how is such a concern scientific at all? Memorization is not important; understanding the different types of planets and their characteristics is. The terrestrial planets formed differently than the gas giants, but we don't say that makes one or the other group not planets.

What Eris and Pluto show us is that there is a third class of planets, the dwarf planets (the IAU definition states that dwarf planets are not planets at all, which makes no sense).

What the public should know is that there are two legitimate competing views on this: that of dynamicists, who study objects' orbits and influence on other objects, and that of planetary scientists, who study the geophysical composition of these objects.

Dr. Alan Stern is one of the leading experts on Pluto and the Kuiper Belt in the world as well as the Principal Investigator of NASA's New Horizons mission to Pluto, and he views the IAU decision as "an embarrassment to astronomy." Why not refer people to his comments?

What about the fact that only four percent of the IAU voted on this definition, and most are not planetary scientists but other types of astronomers? Or the fact that the resolution was adopted surreptitiously on the last day of the IAU General Assembly in violation of the IAU's own bylaws, which require a resolution first be vetted by the appropriate committee before being brought to the floor of the General Assembly?

Myers likes to pretend there is no controversy over Pluto. How is it scientific to pretend there is a consensus about a subject when there is not? How is it scientific to ignore some of the world's leading planetary scientists to force a very confusing, vague, and controversial view on the world?

I may be only one out of nearly 7 billion people on this planet, but I went back to school to study astronomy for the express purpose of getting the demotion of Pluto overturned. One would think people like Myers would applaud that sort of involvement with science, but apparently, the only type of science they support is the type that follows their own dogma.

Why do you refer people only to the books and web sites of Dr. Tyson and Mike Brown? What about "Is Pluto A Planet" by Dr. David Weintraub or "The Case for Pluto" by Alan Boyle? What about the Great Planet Debate, a far more open discussion held in August 2008 at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab in Laurel, MD, where in depth discussion made clear that this issue is not resolved and is far more complex that often portrayed. You do the public a disservice by referring people to only one side of an ongoing debate as "truth" when it is one interpretation of truth. It is acts like this that turn people off to science.

Pluto is not just another KBO. Unlike most, it is in a state of hydrostatic equilibrium, meaning it is large enough to be pulled into a round shape by its own gravity, a characteristic of planets and not shapeless asteroids and KBOs. The same is true of Eris. Why is there a problem with having 20 plus planets in our solar system, and how is such a concern scientific at all? Memorization is not important; understanding the different types of planets and their characteristics is. The terrestrial planets formed differently than the gas giants, but we don't say that makes one or the other group not planets.

What Eris and Pluto show us is that there is a third class of planets, the dwarf planets (the IAU definition states that dwarf planets are not planets at all, which makes no sense).

What the public should know is that there are two legitimate competing views on this: that of dynamicists, who study objects' orbits and influence on other objects, and that of planetary scientists, who study the geophysical composition of these objects.

Dr. Alan Stern is one of the leading experts on Pluto and the Kuiper Belt in the world as well as the Principal Investigator of NASA's New Horizons mission to Pluto, and he views the IAU decision as "an embarrassment to astronomy." Why not refer people to his comments?

What about the fact that only four percent of the IAU voted on this definition, and most are not planetary scientists but other types of astronomers? Or the fact that the resolution was adopted surreptitiously on the last day of the IAU General Assembly in violation of the IAU's own bylaws, which require a resolution first be vetted by the appropriate committee before being brought to the floor of the General Assembly?

Myers likes to pretend there is no controversy over Pluto. How is it scientific to pretend there is a consensus about a subject when there is not? How is it scientific to ignore some of the world's leading planetary scientists to force a very confusing, vague, and controversial view on the world?

I may be only one out of nearly 7 billion people on this planet, but I went back to school to study astronomy for the express purpose of getting the demotion of Pluto overturned. One would think people like Myers would applaud that sort of involvement with science, but apparently, the only type of science they support is the type that follows their own dogma.

The controversy does seem to be largely in the United States -- the rest of the world seems fine with the decision.

Laurel, why does it matter to you so much? The definition of 'planet' and subsequent classification gave Pluto its own status as a dwarf planet.

"Pluto is not just another KBO. Unlike most, it is in a state of hydrostatic equilibrium, meaning it is large enough to be pulled into a round shape by its own gravity, a characteristic of planets and not shapeless asteroids and KBOs."

This is EXACTLY what qualifies Pluto as a dwarf planet.

Laurel, why does it matter to you so much? The definition of 'planet' and subsequent classification gave Pluto its own status as a dwarf planet.

"Pluto is not just another KBO. Unlike most, it is in a state of hydrostatic equilibrium, meaning it is large enough to be pulled into a round shape by its own gravity, a characteristic of planets and not shapeless asteroids and KBOs."

This is EXACTLY what qualifies Pluto as a dwarf planet.

"The controversy does seem to be largely in the United States -- the rest of the world seems fine with the decision."

Sorry, but this is a myth spread by supporters of the IAU decision. There are online astronomy groups, forums, and clubs with members from all over the world who have expressed opposition to the this decision. These include people from places as diverse as Singapore, the Philippines, Canada, England, New Zealand, Australia, and various other countries. As an online astronomy student at Swinburne, I "met" students and instructors from all over the world, and there were plenty of people from countries other than the US who are dissatisfied with the IAU definition and believe dwarf planets should be considered planets too.

Stating that a dwarf planet is not a planet at all makes no sense. Neither does a definition based solely on where an object is while ignoring what that object is. The further an object is from its parent star, the larger an orbit it will have to clear. If Earth were placed in Pluto's orbit, it would not be a planet either. A definition that takes the same object and makes it a planet in one location and not a planet in another is essentially worthless.

I have explained my reasons for opposing the IAU decision. I will add that I and many others would be satisfied with an amendment that establishes dwarf planets as a subclass of planets.

You haven't answered any of my questions as to why you are ignoring the fact that so many planetary scientists oppose the IAU definition and why you are referring people only to the writings of scientists who represent one view in this ongoing controversy.

Sorry, but this is a myth spread by supporters of the IAU decision. There are online astronomy groups, forums, and clubs with members from all over the world who have expressed opposition to the this decision. These include people from places as diverse as Singapore, the Philippines, Canada, England, New Zealand, Australia, and various other countries. As an online astronomy student at Swinburne, I "met" students and instructors from all over the world, and there were plenty of people from countries other than the US who are dissatisfied with the IAU definition and believe dwarf planets should be considered planets too.

Stating that a dwarf planet is not a planet at all makes no sense. Neither does a definition based solely on where an object is while ignoring what that object is. The further an object is from its parent star, the larger an orbit it will have to clear. If Earth were placed in Pluto's orbit, it would not be a planet either. A definition that takes the same object and makes it a planet in one location and not a planet in another is essentially worthless.

I have explained my reasons for opposing the IAU decision. I will add that I and many others would be satisfied with an amendment that establishes dwarf planets as a subclass of planets.

You haven't answered any of my questions as to why you are ignoring the fact that so many planetary scientists oppose the IAU definition and why you are referring people only to the writings of scientists who represent one view in this ongoing controversy.

Laurel, I live in Australia (Adelaide, same as Ian, although we have not met) and I am yet to meet a single person who cared about the demotion of Pluto. (I think the closest it got was: "Great. Now we're going to have to come up with new mnemonics to remember the order of the planets.")

Furthermore, your argumentum ad populum about internet groups is fallacious. There is a whole swathe of fora dedicated to people who believe the world as we know it is going to end on 21 December 2012, but that doesn't make the science any more credible.

Your opposition to Pluto's demotion seems to be largely based on emotional attachment. Why does it matter to you (or anyone else) that it is a dwarf planet? It doesn't change Pluto's historical significance. In fact, one could argue that the necessity of reclassifying Pluto gives us a better understanding of the outer edges of the Solar System.

(And I maintain that it does make sense not to classify them as planets, since they're classified as DWARF PLANETS. It is a new category.)

Furthermore, your argumentum ad populum about internet groups is fallacious. There is a whole swathe of fora dedicated to people who believe the world as we know it is going to end on 21 December 2012, but that doesn't make the science any more credible.

Your opposition to Pluto's demotion seems to be largely based on emotional attachment. Why does it matter to you (or anyone else) that it is a dwarf planet? It doesn't change Pluto's historical significance. In fact, one could argue that the necessity of reclassifying Pluto gives us a better understanding of the outer edges of the Solar System.

(And I maintain that it does make sense not to classify them as planets, since they're classified as DWARF PLANETS. It is a new category.)

The Internet groups, fora, and clubs to which I refer are populated by amateur astronomers and people with a great deal of knowledge about astronomy. These groups definitely have a higher degree of credibility than ad hoc conspiracy groups. I have also had personal communication with many individuals within these groups.

I have also met professional astronomers at various conferences, including the Great Planet Debate held last year at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab and other astronomy-related events and have encountered scientists from all over the world who oppose the IAU decision. Of course, that does not mean that there aren't many who simply don't care or believe the other way. I'm simply reporting what I have experienced and researched.

The same is true regarding my interactions with students and faculty at Swinburne. I naturally do not feel comfortable naming specific individuals without their permission but suffice it to say there are many from around the world who reject the IAU definition.

Of course, planetary science is only one part of astronomy, so it makes sense that there are many amateur and professional astronomers, possibly even the majority of both groups, who do not care about this issue one way or the other.

I and many others, including leading planetary scientists, argue the exact opposite, that the IAU definition not only fails to give us a better understanding of the solar system, but is confusing and vague in its requirement that an object "clear its orbit" and problematic due to the issues I raised in my previous post--mostly the fact that it could result in the absurdity of the same object being a planet in one location and not a planet in another.

The term "dwarf planet" is a noun modified by an adjective. It makes no linguistic sense to say a dwarf planet is not a planet at all. If that was the intent, then those who crafted the resolution should have picked another word, especially since the term "dwarf" is used in astronomy as an adjective--dwarf stars are still stars, and dwarf galaxies are still galaxies.

Your argument that my position is based on "emotional attachment" is a strawman used by supporters of the IAU decision. If they cannot explain why someone has strong convictions about something, they simply attribute to emotions. You should know that such a presumption is not valid.

I am interested in planetary science, as are you, as is Tyson, as is Stern, etc. I want to see a planet definition that takes the geophysical perspective, namely what a planet is, into account as well as the dynamical perspective. Do you ask the other people above why they care about this? If not, why not?

And you have still not answered any of my questions regarding the flaws of the IAU definition or why you think it is okay to portray one view as fact when that view does NOT have a consensus among astronomers and is only one view in an ongoing debate.

I have also met professional astronomers at various conferences, including the Great Planet Debate held last year at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab and other astronomy-related events and have encountered scientists from all over the world who oppose the IAU decision. Of course, that does not mean that there aren't many who simply don't care or believe the other way. I'm simply reporting what I have experienced and researched.

The same is true regarding my interactions with students and faculty at Swinburne. I naturally do not feel comfortable naming specific individuals without their permission but suffice it to say there are many from around the world who reject the IAU definition.

Of course, planetary science is only one part of astronomy, so it makes sense that there are many amateur and professional astronomers, possibly even the majority of both groups, who do not care about this issue one way or the other.

I and many others, including leading planetary scientists, argue the exact opposite, that the IAU definition not only fails to give us a better understanding of the solar system, but is confusing and vague in its requirement that an object "clear its orbit" and problematic due to the issues I raised in my previous post--mostly the fact that it could result in the absurdity of the same object being a planet in one location and not a planet in another.

The term "dwarf planet" is a noun modified by an adjective. It makes no linguistic sense to say a dwarf planet is not a planet at all. If that was the intent, then those who crafted the resolution should have picked another word, especially since the term "dwarf" is used in astronomy as an adjective--dwarf stars are still stars, and dwarf galaxies are still galaxies.

Your argument that my position is based on "emotional attachment" is a strawman used by supporters of the IAU decision. If they cannot explain why someone has strong convictions about something, they simply attribute to emotions. You should know that such a presumption is not valid.

I am interested in planetary science, as are you, as is Tyson, as is Stern, etc. I want to see a planet definition that takes the geophysical perspective, namely what a planet is, into account as well as the dynamical perspective. Do you ask the other people above why they care about this? If not, why not?

And you have still not answered any of my questions regarding the flaws of the IAU definition or why you think it is okay to portray one view as fact when that view does NOT have a consensus among astronomers and is only one view in an ongoing debate.

Laurel, I think our argument over "dwarf planet" vs "planet" probably has more to do with semantics than anything else. The way I interpret the IAU's reasoning, we have "dwarf planet" as one category and "[blank] planet" as another; that is, until it requires a modifier, we just leave it without one.

(By the IAU definition, planets have to orbit the Sun, which eliminates any planetary bodies orbiting other stars. I'm surprised more people haven't taken umbrage to that.)

I wouldn't necessarily have a problem with dwarf planets being reclassified as subclass of planets, given a better definition of both. I agree that it would make the nomenclature more consistent with other areas of astronomy. I'm not sure if the addition of the "plutoid" category helps or hinders this, either. The next meeting of the IAU is next month, so maybe there's hope for us all yet.

"Do you ask the other people above why they care about this? If not, why not?"

To be perfectly frank, this is the first discussion I've got into about it at all (beyond the drinking-with-friends style of discussion). I am genuinely curious, though. What is it about Pluto's classification particularly that causes so much controversy? (Going back to the original post, I guess Mooney and Kirshenbaum were right after all! I still maintain that the controversy is bigger in the USA than elsewhere.)

As for the emotional attachment, perhaps I have misread the tone of your comments, and if so, I apologise. (I still find some of the arguments to be lacking consistent logic, though. And yes, I agree that the IAU definition is not entirely logical, either.)

As for why I "think it is okay to portray one view as fact when the view does not have a consensus"? Simply, it gives us a definition to start with. Planets are a bit like pornography, to make a crude comparison -- "I can't define it, but I know it when I see it." I expect the IAU will revise its current definition in time. (Maybe next month!) But I believe that criticism is not enough -- anyone assailing their definition should be prepared to provide a better one.

Ultimately, what I think both sides of this argument tell us is that we know very little about the Solar System (particularly trans-Neptunian), let alone the rest of the universe.

(By the IAU definition, planets have to orbit the Sun, which eliminates any planetary bodies orbiting other stars. I'm surprised more people haven't taken umbrage to that.)

I wouldn't necessarily have a problem with dwarf planets being reclassified as subclass of planets, given a better definition of both. I agree that it would make the nomenclature more consistent with other areas of astronomy. I'm not sure if the addition of the "plutoid" category helps or hinders this, either. The next meeting of the IAU is next month, so maybe there's hope for us all yet.

"Do you ask the other people above why they care about this? If not, why not?"

To be perfectly frank, this is the first discussion I've got into about it at all (beyond the drinking-with-friends style of discussion). I am genuinely curious, though. What is it about Pluto's classification particularly that causes so much controversy? (Going back to the original post, I guess Mooney and Kirshenbaum were right after all! I still maintain that the controversy is bigger in the USA than elsewhere.)

As for the emotional attachment, perhaps I have misread the tone of your comments, and if so, I apologise. (I still find some of the arguments to be lacking consistent logic, though. And yes, I agree that the IAU definition is not entirely logical, either.)

As for why I "think it is okay to portray one view as fact when the view does not have a consensus"? Simply, it gives us a definition to start with. Planets are a bit like pornography, to make a crude comparison -- "I can't define it, but I know it when I see it." I expect the IAU will revise its current definition in time. (Maybe next month!) But I believe that criticism is not enough -- anyone assailing their definition should be prepared to provide a better one.

Ultimately, what I think both sides of this argument tell us is that we know very little about the Solar System (particularly trans-Neptunian), let alone the rest of the universe.

I agree that this argument makes it clear that we know very little about the outer solar system. In fact, at a panel discussion in March at the American Museum of Natural History in NYC, even Neil de Grasse Tyson admitted that planetary science is in its infancy, and it may be too early to be defining the term planet, especially in light of new discoveries certain to come in this and other solar systems.

The IAU definition requiring that planetary bodies orbit the Sun is ridiculous in and of itself in a time when we are rapidly discovering extra-solar planets. This is yet another reason why it has been contested. How can we have one standard for our solar system and another (or none) for all others? Isn't that going back to Earth being the center of everything?

We have in fact discovered exoplanet systems where gas giants have highly elliptical orbits. In one system, a hot Jupiter has a comet-like orbit while in another, two gas giants orbit in a 3:2 resonance, meaning they cross one another's orbits, and therefore would not meet the IAU definition for being considered a planet.

I admit that as a writer, I probably put more value on semantics than the average person. This combined with my fascination with the solar system likely explains my strong convictions regarding the wrongfulness of the IAU definition and insistence that dwarf planets be reclassified as a subclass of planets.

I also feel strongly that this entire matter should not be left solely to the IAU. Many planetary scientists do not belong to the IAU at all. Most IAU members are other types of astronomers. The European Geophysical Union and the American Geophysical Union continue to conduct their own discussions on planet definition. Depending only on the IAU when so far they have not done a very good job in this area is not necessarily the best route to go on this.

Perhaps it is just my bias, but I believe it is better to present two competing definitions with the rationale for each rather than just one, especially a flawed one, as a starting point. Scientists who reject the IAU definition have provided what they believe is a better alternative. Just read any writings by Dr. Stern on this. Saying they haven't provided an alternate definition is not true. In the interest of fairness and trust in people's ability to sift through the facts and reason for themselves, I cannot support any portrayal of one viewpoint in an ongoing debate, even as a starting point, as fact without presenting the alternative as it has been laid out by quite a number of planetary scientists.

The IAU definition requiring that planetary bodies orbit the Sun is ridiculous in and of itself in a time when we are rapidly discovering extra-solar planets. This is yet another reason why it has been contested. How can we have one standard for our solar system and another (or none) for all others? Isn't that going back to Earth being the center of everything?

We have in fact discovered exoplanet systems where gas giants have highly elliptical orbits. In one system, a hot Jupiter has a comet-like orbit while in another, two gas giants orbit in a 3:2 resonance, meaning they cross one another's orbits, and therefore would not meet the IAU definition for being considered a planet.

I admit that as a writer, I probably put more value on semantics than the average person. This combined with my fascination with the solar system likely explains my strong convictions regarding the wrongfulness of the IAU definition and insistence that dwarf planets be reclassified as a subclass of planets.

I also feel strongly that this entire matter should not be left solely to the IAU. Many planetary scientists do not belong to the IAU at all. Most IAU members are other types of astronomers. The European Geophysical Union and the American Geophysical Union continue to conduct their own discussions on planet definition. Depending only on the IAU when so far they have not done a very good job in this area is not necessarily the best route to go on this.

Perhaps it is just my bias, but I believe it is better to present two competing definitions with the rationale for each rather than just one, especially a flawed one, as a starting point. Scientists who reject the IAU definition have provided what they believe is a better alternative. Just read any writings by Dr. Stern on this. Saying they haven't provided an alternate definition is not true. In the interest of fairness and trust in people's ability to sift through the facts and reason for themselves, I cannot support any portrayal of one viewpoint in an ongoing debate, even as a starting point, as fact without presenting the alternative as it has been laid out by quite a number of planetary scientists.

Lauren wrote: "Pluto is not just another KBO. Unlike most, it is in a state of hydrostatic equilibrium, meaning it is large enough to be pulled into a round shape by its own gravity, a characteristic of planets and not shapeless asteroids and KBOs."

For rocky worlds, hydrostatic equilibrium is reached with a diameter of 700-800 Km, for icy worlds around 400-500Km. This means that Ceres, Orcus, Quaoar, Ixus, Sedna, Makemake at the minimum are planets under this definition. There are 11 KBO's with a diameter above 1000 Km, which makes them all spherical, and there are a lot more KBO's between 500 Km and 1000 Km (which will also be mostly spherical, eg Varuna).

Pluto is just another KBO, it's at the top range of currently known KBO diameters, but by no means unique. Just having "it's spherical" as a rule has the advantage of simplicity, but raises a whole range of problems.

But the bottom line is Mooney and co. misrepresent the whole issue. There was a clear scientific need for a decision, forced by Eris. The decision had been a long time coming, accompanied by a lot of high profile debate. The decision may have been unpopular, but Mooney and co. completely misrepresent it.

For rocky worlds, hydrostatic equilibrium is reached with a diameter of 700-800 Km, for icy worlds around 400-500Km. This means that Ceres, Orcus, Quaoar, Ixus, Sedna, Makemake at the minimum are planets under this definition. There are 11 KBO's with a diameter above 1000 Km, which makes them all spherical, and there are a lot more KBO's between 500 Km and 1000 Km (which will also be mostly spherical, eg Varuna).

Pluto is just another KBO, it's at the top range of currently known KBO diameters, but by no means unique. Just having "it's spherical" as a rule has the advantage of simplicity, but raises a whole range of problems.

But the bottom line is Mooney and co. misrepresent the whole issue. There was a clear scientific need for a decision, forced by Eris. The decision had been a long time coming, accompanied by a lot of high profile debate. The decision may have been unpopular, but Mooney and co. completely misrepresent it.

First, my name is Laurel, not Lauren.

I disagree that there was a clear scientific need for a decision. Since we have a spacecraft on its way to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, we know we will have much more data in the near future. There is no reason to rush to a decision when we know that, as Tyson himself says, "planetary science is still in its infancy," and we will have a lot more data on which to make an informed decision within only a few years.

Yes, I consider Ceres, Orcus, Quaoar, Ixus, Sedna, Makemake, etc. to be planets. You are making an assumption that there is something inherently problematic about having a large number of planets. Why is this? Hydrostatic equilibrium is a very clear boundary separating those objects large enough to be shaped by their own gravity and those shaped only by chemical bonds. While there will always be a few objects on the fringes, neither Pluto nor the bodies you listed above fall into that category.

I wholeheartedly disagree with your statement that Pluto is just another KBO. It is not. The overwhelming majority of KBOs are not in hydrostatic equilibrium. Those that are in this state have attained a property in common with planets, and not recognizing this blurs this important distinction.

If we establish dwarf planets as a subclass of planets, then we can say our solar system has four terrestrial planets, four gas giants, and possibly up to 500 dwarf planets. We can also further subcategorize dwarf planets if there is a clear need to distinguish between the larger ones and the smaller ones with diameters between 500 and 1000 kilometers in diameter.

I believe that the point of Mooney and Kirschenbaum in presenting this debate is to show that the public recognized scientists using a very flawed process to reach a decision and then attempting to impose that decision on the entire world in a pretense that they had a consensus on it when they didn't. The entire issue was handled very poorly; it was rushed through on the last day of a conference due largely to concerns by IAU members to avoid looking bad--as opposed to genuine concerns about coming up with a useful definition. The IAU failed miserably in this process, which is an example of how scientists should not be going about making decisions.

I disagree that there was a clear scientific need for a decision. Since we have a spacecraft on its way to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, we know we will have much more data in the near future. There is no reason to rush to a decision when we know that, as Tyson himself says, "planetary science is still in its infancy," and we will have a lot more data on which to make an informed decision within only a few years.

Yes, I consider Ceres, Orcus, Quaoar, Ixus, Sedna, Makemake, etc. to be planets. You are making an assumption that there is something inherently problematic about having a large number of planets. Why is this? Hydrostatic equilibrium is a very clear boundary separating those objects large enough to be shaped by their own gravity and those shaped only by chemical bonds. While there will always be a few objects on the fringes, neither Pluto nor the bodies you listed above fall into that category.

I wholeheartedly disagree with your statement that Pluto is just another KBO. It is not. The overwhelming majority of KBOs are not in hydrostatic equilibrium. Those that are in this state have attained a property in common with planets, and not recognizing this blurs this important distinction.

If we establish dwarf planets as a subclass of planets, then we can say our solar system has four terrestrial planets, four gas giants, and possibly up to 500 dwarf planets. We can also further subcategorize dwarf planets if there is a clear need to distinguish between the larger ones and the smaller ones with diameters between 500 and 1000 kilometers in diameter.

I believe that the point of Mooney and Kirschenbaum in presenting this debate is to show that the public recognized scientists using a very flawed process to reach a decision and then attempting to impose that decision on the entire world in a pretense that they had a consensus on it when they didn't. The entire issue was handled very poorly; it was rushed through on the last day of a conference due largely to concerns by IAU members to avoid looking bad--as opposed to genuine concerns about coming up with a useful definition. The IAU failed miserably in this process, which is an example of how scientists should not be going about making decisions.

PS. I've been late commenting because I had to nick off for family business. I'll be a little late commenting again. (Waves to MattR)

This Kornfeld maroon is trolling about this all over the Web. I don't know what her problem is, but it probably needs to be dealt with by trained professionals. There is no point in attempting to reason with her.

This is undoubtedly another semantic issue (and I think your post is otherwise terrific), but isn't the ordinary nomenclature to the effect that Earth revolves around the Sun once per year and rotates on its axis once per day?

Looking at your chart, I fear that I would have gotten the Earth-rotates-annually question "wrong," in that I'm not familiar with a planet (or, er, whatever) orbiting a star being called "rotation."

Looking at your chart, I fear that I would have gotten the Earth-rotates-annually question "wrong," in that I'm not familiar with a planet (or, er, whatever) orbiting a star being called "rotation."

@Steve LaBonne

I'm "trolling" all over the web? There's no reasoning with me? If you look at my comments, you will see that I've presented very reasonable arguments. You may disagree with them, but resorting to an ad hominem attack does nothing to promote your viewpoint. In fact, in many cases, I and others who think differently have respectfully agreed to disagree.

Why do you not accuse the IAU and its proponents of "trolling?"

It is the leadership of the IAU who needs the professional help of planetary scientists to fix the mess they created in 2006. Personally, I am now studying astronomy through a terrific program at Swinburne University, so I am getting all the assistance I need towards strengthening my knowledge in this field.

I'm "trolling" all over the web? There's no reasoning with me? If you look at my comments, you will see that I've presented very reasonable arguments. You may disagree with them, but resorting to an ad hominem attack does nothing to promote your viewpoint. In fact, in many cases, I and others who think differently have respectfully agreed to disagree.

Why do you not accuse the IAU and its proponents of "trolling?"

It is the leadership of the IAU who needs the professional help of planetary scientists to fix the mess they created in 2006. Personally, I am now studying astronomy through a terrific program at Swinburne University, so I am getting all the assistance I need towards strengthening my knowledge in this field.

I'm "trolling" all over the web? There's no reasoning with me?

Yes and yes. I seriously suggest seeking professional help for this delusional mania of yours.

Though your trolling does help to spread the word about the blatant idiocy of Mooneybaum's Pluto chapter, so I suppose I should encourage you...

Yes and yes. I seriously suggest seeking professional help for this delusional mania of yours.

Though your trolling does help to spread the word about the blatant idiocy of Mooneybaum's Pluto chapter, so I suppose I should encourage you...

Actually, Mooney and Kirschenbaum's book is doing quite well in spite of a few vocal opponents.

There are strong scientific arguments for Pluto retaining its planet status.

Resorting to personal attacks indicates you are unable to provide legitimate, logical responses to these arguments.

There are strong scientific arguments for Pluto retaining its planet status.

Resorting to personal attacks indicates you are unable to provide legitimate, logical responses to these arguments.

Laurel (not Lauren, sorry, the typo king strikes again) wrote: Stating that a dwarf planet is not a planet at all makes no sense.. That’s precisely what we did with the Minor Planets back in 1846. Ceres, Vesta, Pallas etc. etc. are all Minor Planets, and not Planets.

“I disagree that there was a clear scientific need for a decision. Since we have a spacecraft on its way to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, we know we will have much more data in the near future.”

While a number of large objects pushing the Pluto limit had been found, it was the discovery of Xena/Eris, larger than Pluto, that made the need for a determination urgent. The status of Eris needed to be resolved well before any spacecraft arrived. And the spacecraft, while providing a wealth of information, would tell us nothing that about Pluto we did not already know vis a vis planetary status (how big it was, was it spherical, whether it cleared its local area). As it was, Eris was in limbo for more than a year.

While you may disagree, it was clear that planetary scientists (both pro and anti- Pluto) did saw a pressing need for a decision.

However, the main issue, which you keep missing is not what resolution was made, but M&K’s representation of the process.

1) The issue was not sudden as they claim, but had been a high profile debate since 2001.

2) The Pluto affair was driven by scientific issues, culminating in the high profile discovery of an object bigger than Pluto. The criteria were based on physical properties, not arbitrary dividing lines (and remember that the IAU criteria would have kept Pluto as a planet)

3) The IAU did care what the public thought, contrary to M&K’s claims, and went to great lengths to present the argument and the proceedings to the public in a variety of fora. They especially paid great attention to making sure the issue was presented in an easy to understand manner (the televised “playdo planet” presentation for example)

4) Many astronomers, not just the IAU presented information in a variety of settings (talks, newspaper articles, online materials such as web pages) in the lead up to the vote

Virtually every aspect of M&K’s description of the process is wrong. The outcome of the final vote was controversial, but M&K’s contention that astronomers did not care about what the public thought and failed to communicate with the public is completely and utterly wrong.

Given the significant resources both the IAU and individual astronomers put into informing the public, indeed basically doing everything M&K said scientists should do (and astronomers saw the Pluto affair as a golden opportunity to explain the importance of modern planetary science and its exciting discoveries) what more could the astronomers have done? Hung around on street corners and handed out leaflets? Held Kuiper Belt parades? M&K offer no clue, they offer a mere drive-by account of naughty scientists “poking the public with a stick”, which is as far from the truth as you could possibly get.

Again, this issue is NOT the result of the final vote, (which most people thought would go for keeping Pluto and adding Eris; this was the model produced by the IAU committee of respected researchers and science communicators and the pre-meeting press releases emphasised this model. It was the planetary scientist members of the IAU that put up the no-Pluto model, not the IAU or its committee devoted to the Pluto question). Regardless of how you feel about the final vote, M&K’s account of the lead up to it, and the science communication effort by the IAU (and all the other astronomers) was dead wrong.

“I disagree that there was a clear scientific need for a decision. Since we have a spacecraft on its way to Pluto and the Kuiper Belt, we know we will have much more data in the near future.”

While a number of large objects pushing the Pluto limit had been found, it was the discovery of Xena/Eris, larger than Pluto, that made the need for a determination urgent. The status of Eris needed to be resolved well before any spacecraft arrived. And the spacecraft, while providing a wealth of information, would tell us nothing that about Pluto we did not already know vis a vis planetary status (how big it was, was it spherical, whether it cleared its local area). As it was, Eris was in limbo for more than a year.

While you may disagree, it was clear that planetary scientists (both pro and anti- Pluto) did saw a pressing need for a decision.

However, the main issue, which you keep missing is not what resolution was made, but M&K’s representation of the process.

1) The issue was not sudden as they claim, but had been a high profile debate since 2001.

2) The Pluto affair was driven by scientific issues, culminating in the high profile discovery of an object bigger than Pluto. The criteria were based on physical properties, not arbitrary dividing lines (and remember that the IAU criteria would have kept Pluto as a planet)

3) The IAU did care what the public thought, contrary to M&K’s claims, and went to great lengths to present the argument and the proceedings to the public in a variety of fora. They especially paid great attention to making sure the issue was presented in an easy to understand manner (the televised “playdo planet” presentation for example)

4) Many astronomers, not just the IAU presented information in a variety of settings (talks, newspaper articles, online materials such as web pages) in the lead up to the vote

Virtually every aspect of M&K’s description of the process is wrong. The outcome of the final vote was controversial, but M&K’s contention that astronomers did not care about what the public thought and failed to communicate with the public is completely and utterly wrong.

Given the significant resources both the IAU and individual astronomers put into informing the public, indeed basically doing everything M&K said scientists should do (and astronomers saw the Pluto affair as a golden opportunity to explain the importance of modern planetary science and its exciting discoveries) what more could the astronomers have done? Hung around on street corners and handed out leaflets? Held Kuiper Belt parades? M&K offer no clue, they offer a mere drive-by account of naughty scientists “poking the public with a stick”, which is as far from the truth as you could possibly get.

Again, this issue is NOT the result of the final vote, (which most people thought would go for keeping Pluto and adding Eris; this was the model produced by the IAU committee of respected researchers and science communicators and the pre-meeting press releases emphasised this model. It was the planetary scientist members of the IAU that put up the no-Pluto model, not the IAU or its committee devoted to the Pluto question). Regardless of how you feel about the final vote, M&K’s account of the lead up to it, and the science communication effort by the IAU (and all the other astronomers) was dead wrong.

As a postscript, today I was talking about this with a friend on the train. An intelligent man, interested in the cosmos, keeping abreast of developments though a variety of sources, he had no idea that Pluto had been demoted. If even a raging controversy can’t get through to intelligent, well read people (in both old and new media), how can ordinary science communication get through. Do M&K have an answer for that?

"That’s precisely what we did with the Minor Planets back in 1846. Ceres, Vesta, Pallas etc. etc. are all Minor Planets, and not Planets."

Just because a decision to adopt a term based on incorrect usage was done once does not justify doing it again and again. In fact, the more accurate term for most of the bodies referred to as "minor planets" is "planetoids," which means planet-like objects. "Asteroid is not a particularly good "term either, as

it means star-like and was suggested by William Herschel because the small size of these objects made them appear as points of light rather than as disks through the telescopes of the day.

Now that we know Ceres is in a state of hydrostatic equilibrium, it should be reclassified as a small planet. The same may be true of Vesta and possibly Pallas.

"While a number of large objects pushing the Pluto limit had been found, it was the discovery of Xena/Eris, larger than Pluto, that made the need for a determination urgent. The status of Eris needed to be resolved well before any spacecraft arrived."

Why would it have been a problem to simply declare Eris the tenth planet, as we know it is spherical and slightly more massive than Pluto. The only reason the status of Eris was in limbo at all was a concocted issue by some scientists who believe we need to keep the number of planets in our solar system low.

Just because a decision to adopt a term based on incorrect usage was done once does not justify doing it again and again. In fact, the more accurate term for most of the bodies referred to as "minor planets" is "planetoids," which means planet-like objects. "Asteroid is not a particularly good "term either, as

it means star-like and was suggested by William Herschel because the small size of these objects made them appear as points of light rather than as disks through the telescopes of the day.

Now that we know Ceres is in a state of hydrostatic equilibrium, it should be reclassified as a small planet. The same may be true of Vesta and possibly Pallas.

"While a number of large objects pushing the Pluto limit had been found, it was the discovery of Xena/Eris, larger than Pluto, that made the need for a determination urgent. The status of Eris needed to be resolved well before any spacecraft arrived."

Why would it have been a problem to simply declare Eris the tenth planet, as we know it is spherical and slightly more massive than Pluto. The only reason the status of Eris was in limbo at all was a concocted issue by some scientists who believe we need to keep the number of planets in our solar system low.

"It was the planetary scientist members of the IAU that put up the no-Pluto model, not the IAU or its committee devoted to the Pluto question)."

This is simply incorrect. The alternate resolution ultimately adopted by the IAU was put together and rushed through by the dynamicists, not the planetary scientists.

There are several important points to note regarding the process by which the IAU reached and communicated its decision on planet definition.

First, it should have been obvious to anyone paying attention to astronomy that demoting Pluto would be unpalatable to much of the general public. In 1999, a proposal to reclassify Pluto as a "minor planet" drew intense objections from the public and scientists alike.

In making its decision, the IAU did not even respect its own bylaws and its own members. Not only did the IAU reject the recommendation of its own committee; but organizers of the resolution ultimately adopted threw it together so hastily that changes were still being made to the text during the session. Jocelyn Bell Burnell's top priority, when faced with serious questions, was to move the session along. Notably, one of the members stated that if the IAU did not adopt a planet definition, the would "look like idiots" to the rest of the world. There was clearly a motive of preserving the IAU's image and getting something passed, even if it was poorly put together.

Astronomers not at the General Assembly may have communicated with the public via the Internet and newspaper articles, but ultimately, the input of a large contingent of planetary scientists, those who wanted a definition that takes into account geophysical composition, was ignored when the resolution was adopted.

What more could the IAU have done? First, they could have adhered to their own bylaws and not allowed a resolution on the floor that had not been first vetted by the appropriate committee.

Second, they could have allowed electronic voting, which would have made it possible for every IAU member to vote, not just those in the room on the last day of a two-week conference.

Third, they could have more openly solicited both public opinion as well as input from planetary scientists who are not IAU members and from amateur astronomers as well. Amateur astronomy groups often act as the intermediaries who communicate astronomy with the public. Groups like the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, which exist in every country, interact regularly with the public and could serve an important function in conveying public opinion to professional astronomers and vice versa.

Fourth, when it became obvious that the only way to adopt a planet definition was for the IAU to rush through a resolution thrown together at the last minute, the group's leadership, in the interest of being thorough and following an open process should have postponed any decision until the next General Assembly, sending the issue back to its own committee for reconsideration.

This is simply incorrect. The alternate resolution ultimately adopted by the IAU was put together and rushed through by the dynamicists, not the planetary scientists.

There are several important points to note regarding the process by which the IAU reached and communicated its decision on planet definition.

First, it should have been obvious to anyone paying attention to astronomy that demoting Pluto would be unpalatable to much of the general public. In 1999, a proposal to reclassify Pluto as a "minor planet" drew intense objections from the public and scientists alike.

In making its decision, the IAU did not even respect its own bylaws and its own members. Not only did the IAU reject the recommendation of its own committee; but organizers of the resolution ultimately adopted threw it together so hastily that changes were still being made to the text during the session. Jocelyn Bell Burnell's top priority, when faced with serious questions, was to move the session along. Notably, one of the members stated that if the IAU did not adopt a planet definition, the would "look like idiots" to the rest of the world. There was clearly a motive of preserving the IAU's image and getting something passed, even if it was poorly put together.

Astronomers not at the General Assembly may have communicated with the public via the Internet and newspaper articles, but ultimately, the input of a large contingent of planetary scientists, those who wanted a definition that takes into account geophysical composition, was ignored when the resolution was adopted.

What more could the IAU have done? First, they could have adhered to their own bylaws and not allowed a resolution on the floor that had not been first vetted by the appropriate committee.

Second, they could have allowed electronic voting, which would have made it possible for every IAU member to vote, not just those in the room on the last day of a two-week conference.

Third, they could have more openly solicited both public opinion as well as input from planetary scientists who are not IAU members and from amateur astronomers as well. Amateur astronomy groups often act as the intermediaries who communicate astronomy with the public. Groups like the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, which exist in every country, interact regularly with the public and could serve an important function in conveying public opinion to professional astronomers and vice versa.

Fourth, when it became obvious that the only way to adopt a planet definition was for the IAU to rush through a resolution thrown together at the last minute, the group's leadership, in the interest of being thorough and following an open process should have postponed any decision until the next General Assembly, sending the issue back to its own committee for reconsideration.

Laurel,

Professional astronomers felt a need, to clarify among themselves to further expand their work, to make this distinction.

And they felt that there was no reason not to let laypeople know of this, anymore than they would keep anything else a "secret".

The professionals, to whom it will be useful, will use it such.

Anyone who doesn't want to use the definition the professionals use, doesn't have to - it's not a law that you have to. Keep using any term that you want, and let each scientist use what s/he finds useful to use among his colleagues.

Even though they felt they needed to do that for their work, you think that either:

- they shouldn't do it, because some don't like it

OR

- you know better than they do what they need to do their job

Either reason: how incredibly arrogant of you.

Professional astronomers felt a need, to clarify among themselves to further expand their work, to make this distinction.

And they felt that there was no reason not to let laypeople know of this, anymore than they would keep anything else a "secret".

The professionals, to whom it will be useful, will use it such.

Anyone who doesn't want to use the definition the professionals use, doesn't have to - it's not a law that you have to. Keep using any term that you want, and let each scientist use what s/he finds useful to use among his colleagues.

Even though they felt they needed to do that for their work, you think that either:

- they shouldn't do it, because some don't like it

OR

- you know better than they do what they need to do their job

Either reason: how incredibly arrogant of you.

Some professional astronomers felt this way, by no means all.

Many professional astronomers are not using the IAU definition either, as can be seen from these links: http://www.ipetitions.com/petition/planetprotest/

http://www.skyandtelescope.com/news/home/20661469.html?pageSize=0

http://www.sciencenews.org/index/generic/activity/view/id/38770/title/Debates_over_definition_of_planet_continue_and_inspire

http://www.skyandtelescope.com/skytel/beyondthepage/38235059.html

http://flyingsinger.blogspot.com/2009/02/giving-pluto-another-chance.html

Many professional astronomers are not using the IAU definition either, as can be seen from these links: http://www.ipetitions.com/petition/planetprotest/

http://www.skyandtelescope.com/news/home/20661469.html?pageSize=0

http://www.sciencenews.org/index/generic/activity/view/id/38770/title/Debates_over_definition_of_planet_continue_and_inspire

http://www.skyandtelescope.com/skytel/beyondthepage/38235059.html

http://flyingsinger.blogspot.com/2009/02/giving-pluto-another-chance.html

Gosh, you're such a plutotic, Laurel.

Contrary to what you claim, and no-one is suggesting that there aren't some spare fellow plutotics in various hideouts, there is no public controversy whatsoever in Europe about this.

Your profile claims that you are a writer. I find this hard to believe for the following reasons:

Shouldn't a writer know that broadening definitions (e.g.: Planet: Anything round in space) makes the terms useless. It is narrowly defined terms that enables us to talk about anything in the first place. Otherwise we'd just be verb noun conjunction auxiliary verb verb, adverb verb noun conjunction adjective noun.

Furthermore, shouldn't a writer know that "demoting Pluto" is nothing more than an appeal to emotion with no basis in reality? What has Pluto been demoted from? You think that dwarf planets are somewhat "less" than planets? How so? That are just your personal superimposed values and irrational feelings; nothing else. The notion that you're just trolling seems indeed appropriate.

Contrary to what you claim, and no-one is suggesting that there aren't some spare fellow plutotics in various hideouts, there is no public controversy whatsoever in Europe about this.

Your profile claims that you are a writer. I find this hard to believe for the following reasons:

Shouldn't a writer know that broadening definitions (e.g.: Planet: Anything round in space) makes the terms useless. It is narrowly defined terms that enables us to talk about anything in the first place. Otherwise we'd just be verb noun conjunction auxiliary verb verb, adverb verb noun conjunction adjective noun.

Furthermore, shouldn't a writer know that "demoting Pluto" is nothing more than an appeal to emotion with no basis in reality? What has Pluto been demoted from? You think that dwarf planets are somewhat "less" than planets? How so? That are just your personal superimposed values and irrational feelings; nothing else. The notion that you're just trolling seems indeed appropriate.

There is a public controversy about this that is ongoing among planetary scientists. Denying that fact does not make it so.

Preference for broadening versus narrowing the definition of terms likely depends on the individual writer and the specific topic at hand. If there are many types of objects that fit one category, using a broad, overarching term does not make that term useless. In the case of planet, I share the view of astronomers like Dr. Mark Sykes, who want to see "planet" as a broad, overarching umbrella term encompassing any non-self-luminous spheroidal body orbiting a star. We can then differentiate the various types of planets through the use of subcategories: terrestrial planets, gas giants, ice giants, dwarf planets, hot Jupiters, super Earths, etc.

There are plenty of scientific classification schemes in which a broad category encompasses a wide variety of objects with several key features in common, and subcategories are used to distinguish within that larger category. The term "mammal" includes bats, whales and dolphins, bears, monkeys, canines, felines, humans, etc. Subcategories such as "primate" distinguish the specific types of mammals, and even those subcategories have subcategories of their own.

The argument that opposition to the demotion of Pluto is based on emotion is a straw man used by those who support the IAU decision. This has nothing to do with emotion or with a sense that dwarf planets are somehow less than planets. The concern of those who oppose the IAU decision is that it classifies objects solely by where they are while ignoring what they are and that it says dwarf planets are not planets. Being in hydrostatic equilibrium, dwarf planets have this central characteristic of planets, only they are smaller to the point that they do not gravitationally dominate their orbits. Dr. Stern is the person who actually coined the term "dwarf planets," and he intended the term to indicate a subcategory of planets, not to name a separate class of objects that aren't considered planets at all.

As for trolling, the commonly understood definition is deliberately making inflammatory remarks on Internet sites to rile people up and start less than friendly arguments. I am attempting to portray the other side of this debate with rational, scientific arguments. You may not agree with that position, but it hardly constitutes trolling.

Preference for broadening versus narrowing the definition of terms likely depends on the individual writer and the specific topic at hand. If there are many types of objects that fit one category, using a broad, overarching term does not make that term useless. In the case of planet, I share the view of astronomers like Dr. Mark Sykes, who want to see "planet" as a broad, overarching umbrella term encompassing any non-self-luminous spheroidal body orbiting a star. We can then differentiate the various types of planets through the use of subcategories: terrestrial planets, gas giants, ice giants, dwarf planets, hot Jupiters, super Earths, etc.

There are plenty of scientific classification schemes in which a broad category encompasses a wide variety of objects with several key features in common, and subcategories are used to distinguish within that larger category. The term "mammal" includes bats, whales and dolphins, bears, monkeys, canines, felines, humans, etc. Subcategories such as "primate" distinguish the specific types of mammals, and even those subcategories have subcategories of their own.

The argument that opposition to the demotion of Pluto is based on emotion is a straw man used by those who support the IAU decision. This has nothing to do with emotion or with a sense that dwarf planets are somehow less than planets. The concern of those who oppose the IAU decision is that it classifies objects solely by where they are while ignoring what they are and that it says dwarf planets are not planets. Being in hydrostatic equilibrium, dwarf planets have this central characteristic of planets, only they are smaller to the point that they do not gravitationally dominate their orbits. Dr. Stern is the person who actually coined the term "dwarf planets," and he intended the term to indicate a subcategory of planets, not to name a separate class of objects that aren't considered planets at all.

As for trolling, the commonly understood definition is deliberately making inflammatory remarks on Internet sites to rile people up and start less than friendly arguments. I am attempting to portray the other side of this debate with rational, scientific arguments. You may not agree with that position, but it hardly constitutes trolling.

Ian, I followed you here from Chad Orzel's blog. I don't have more to say on M&K's interpretation of the planetary definition controversy, but I'd just like to pick up on one point Laurel has made:

The alternate resolution ultimately adopted by the IAU was put together and rushed through by the dynamicists, not the planetary scientists.

This is a false distinction. They were planetary scientists who happen to be dynamicists.

If you go here:

http://astro.cas.cz/nuncius/appendix.html#tancredi

you will see the internal (but public at the time, as far as I know) bulletin put out by the IAU on Resolution 5 when it became apparent that it wasn't going to be an easy ride. If you Google (or better, search on the Arxiv) the names of the signatories, you will see that they are mainly scientists who study asteroids and the Kuiper Belt. Division III, which they mention, is the Division for Planetary Systems Science. These are the exactly the group of people whose work is most concerned with the effect of the definition.

I think that this became such a big deal precisely because it was a disagreement within the relatively small community of planetary scientists. The rift went to the core, and so the public had no authoritative group to look to.

I'm only cluttering Ian's blog here because it strikes me that the crusade by Stern, Sykes and others has potential to do real damage to the scientific community (and thence the public's perception of science) by, in effect though perhaps not in intention, pointing at a subgroup of planetary scientists and saying "you aren't part of us". Pluto's status isn't worth that.

The alternate resolution ultimately adopted by the IAU was put together and rushed through by the dynamicists, not the planetary scientists.